Stanley Jaki:

A Life Devoted to the Relationship

Between Science and Faith

Antonio Giovanni Colombo

This text reflects a presentation given at the Seton Hall Universiy (New Jersey) on April 24, 2024. For details about the event, see here.

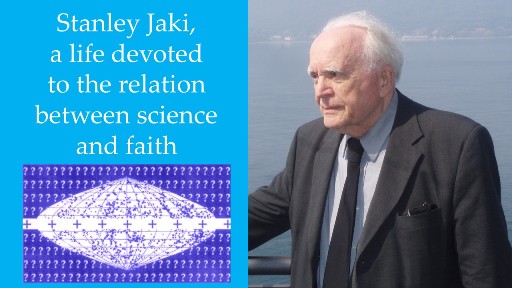

The image on the lower right side of the slide, created by Father Stanley Jaki himself, is taken from the cover of the book Questions on Science and Religion, [1] and symbolizes the heart of the matter: the background is full of question marks (Questions), superimposed with an oval image of the universe, produced by the cosmic microwave background radiation images (Science). In the center of the image, where our galaxy would be, is a series of crosses, to represent the Christian faith (Religion). The book is an excellent starting point to approach the work of Father Jaki, since it engages the vast majority of the main themes about which he wrote.

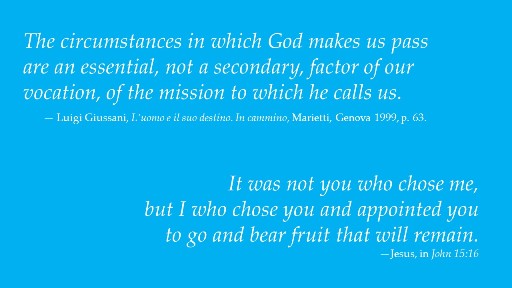

The quote on the slide is useful in understanding the path in life taken by Father Jaki: “The circumstances in which God makes us pass are an essential, not a secondary, factor of our vocation, of the mission to which he calls us.” [2] The statement reminds us that God does not intervene in our lives only miraculously, as happened to Saint Paul on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:3-6), but through a series of signs that are sent to us every day, which we are free to follow or not. These signs are what theologically define a vocation, a call. As Jesus himself put it, “it was not you who chose me, but I who chose you and appointed you to go and bear fruit that will remain” (John 15:16). In other words, it happens that our vocation comes to meet us while we are trying to do something else. Father Jaki’s work shows us how he answered his vocation throughout his life.

Father Jaki was born in Győr, Hungary, on August 17, 1924. Before entering the

seminary he had carried out various activities, including rowing, and acting in

an amateur theater group. As a boy scout he achieved the highest rank, Eagle-Scout.

Father Jaki was born in Győr, Hungary, on August 17, 1924. Before entering the

seminary he had carried out various activities, including rowing, and acting in

an amateur theater group. As a boy scout he achieved the highest rank, Eagle-Scout.

He entered the novitiate at the Benedictine Abbey in Pannonhalma in 1942. Pannonhalma is

the most important Hungarian abbey; some of the oldest Hungarian manuscripts

are preserved in its library.

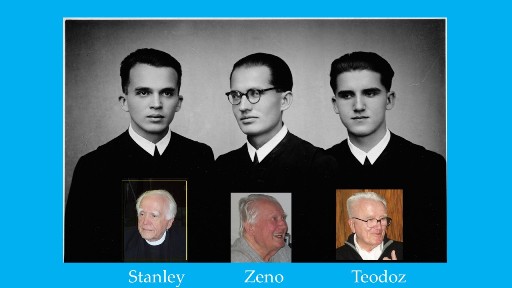

All the brothers in his family followed the same vocation to become Benedictine monks.

The brothers attended a Benedictine high school, in their hometown of Győr.

Father Jaki says he felt that his vocation was the priesthood even from the age of

around seven years old.

[3]

He entered the novitiate at the Benedictine Abbey in Pannonhalma in 1942. Pannonhalma is

the most important Hungarian abbey; some of the oldest Hungarian manuscripts

are preserved in its library.

All the brothers in his family followed the same vocation to become Benedictine monks.

The brothers attended a Benedictine high school, in their hometown of Győr.

Father Jaki says he felt that his vocation was the priesthood even from the age of

around seven years old.

[3]

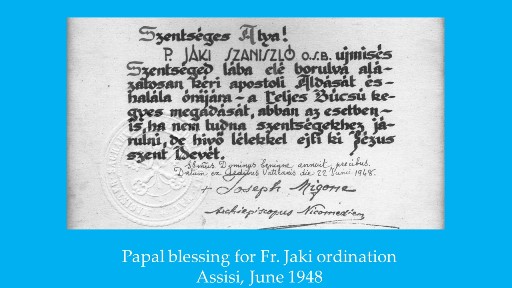

As a seminarian, Father Jaki was sent to Rome in 1947 to complete his studies at the

Pontifical Ateneo Sant’Anselmo. He was ordained a priest in 1948, in Assisi, by

the Benedictine Bishop Mgr. Giuseppe Placido Nicolini.

As a seminarian, Father Jaki was sent to Rome in 1947 to complete his studies at the

Pontifical Ateneo Sant’Anselmo. He was ordained a priest in 1948, in Assisi, by

the Benedictine Bishop Mgr. Giuseppe Placido Nicolini.

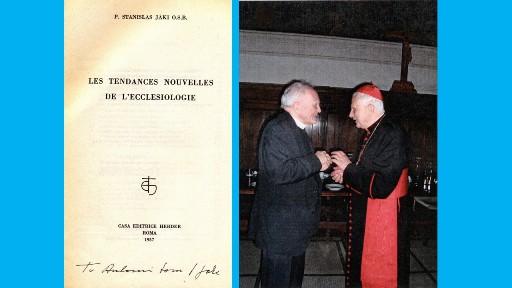

In December 1950 Father Jaki was granted a doctorate in theology; his thesis, written in

French, was titled

Les tendances nouvelles de l’ecclésiologie

(New Trends in Ecclesiology).

[4]

It was published in 1957. A

review of it was made at the time by the

future Card. Ratzinger, who many years later said: “Oh, Father Jaki,

your

Tendances,

which I was most pleased to review, occupies a place of

honor in my library”.

[5]

The book shows the origin of the then current trends in ecclesiology from the

Council of Trento up to the first half of the 20th century, dealing also with

Protestant and Orthodox authors. It was reprinted in 1963, during the Second

Vatican Council.

Of this book, which in a

certain sense defines Jaki as a theologian, we only quote the statement taken

from Saint Augustine with which Father Jaki concludes the book: “Hold then,

most beloved, hold all with one mind to God the Father, and the Church our

Mother.”

[6]

In December 1950 Father Jaki was granted a doctorate in theology; his thesis, written in

French, was titled

Les tendances nouvelles de l’ecclésiologie

(New Trends in Ecclesiology).

[4]

It was published in 1957. A

review of it was made at the time by the

future Card. Ratzinger, who many years later said: “Oh, Father Jaki,

your

Tendances,

which I was most pleased to review, occupies a place of

honor in my library”.

[5]

The book shows the origin of the then current trends in ecclesiology from the

Council of Trento up to the first half of the 20th century, dealing also with

Protestant and Orthodox authors. It was reprinted in 1963, during the Second

Vatican Council.

Of this book, which in a

certain sense defines Jaki as a theologian, we only quote the statement taken

from Saint Augustine with which Father Jaki concludes the book: “Hold then,

most beloved, hold all with one mind to God the Father, and the Church our

Mother.”

[6]

After finishing his studies, Father Jaki did not return to Hungary, due to the

political situation there, in particular to the persecution against religion

carried on by the local Communist regime (of 182 convents, only 6 were still active around 1950).

[7]

Because his thesis had been written in French, he

expected to be sent to France. Instead, he was directed to go to the United

States and arrived in New York on December 21, 1950.

[8]

A week later he arrived at

the Seminary of Saint Vincent, in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and six months later

began what was expected to be a teaching career. He taught systematic theology

at the seminary and French at the adjoining college. In the courses at the

seminary he drew out the omnipotence of God and His creation.

[9]

These theological themes have vast ramifications, affecting both philosophy and science.

After finishing his studies, Father Jaki did not return to Hungary, due to the

political situation there, in particular to the persecution against religion

carried on by the local Communist regime (of 182 convents, only 6 were still active around 1950).

[7]

Because his thesis had been written in French, he

expected to be sent to France. Instead, he was directed to go to the United

States and arrived in New York on December 21, 1950.

[8]

A week later he arrived at

the Seminary of Saint Vincent, in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, and six months later

began what was expected to be a teaching career. He taught systematic theology

at the seminary and French at the adjoining college. In the courses at the

seminary he drew out the omnipotence of God and His creation.

[9]

These theological themes have vast ramifications, affecting both philosophy and science.

Father Jaki wrote in his autobiography,

“I have always been very pleased to read books and learn.”

[10]

This is why, between 1951

and 1954, while he was already teaching, he decided to further his grasp of

physics

[11]

and attended courses in mathematics and physics,

obtaining a bachelor of science degree in physics in 1954.

[12]

However, on

December 9, 1953, his teaching career was interrupted. The “decisive factor”

was an extremely trivial event: the removal of his tonsils.

While this is usually a routine operation,

few days after surgery Father Jaki hemorrhaged in two spots

and was almost voiceless for the next ten years.

What little voice he had was insufficient for teaching,

but it did not prevent him from continuing his studies

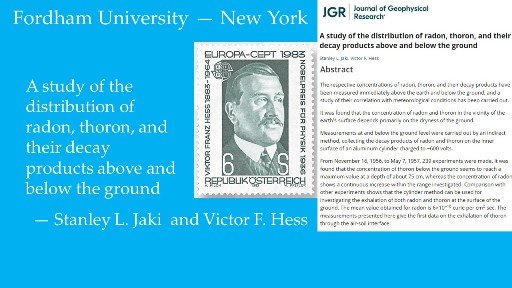

and obtaining a PhD in Physics at the Fordham University in 1957.

[13]

Among his teachers was the 1936

Nobel Prize recipient in Physics, Victor Hess. A partnership arose between the

two, and Father Jaki conducted his research under Dr. Hess’ direction,

presented his dissertation in 1957, and published an article signed

by the two of them in the prestigious

Journal of Geophysical Research.

The thesis had as its title,

A study of the distribution of radon, thoron

(which are rare gases)

and their decay products above and below the ground.

[14]

Even if the title may seem rather abstruse,

radon is the second cause of lung cancer (after smoking).

His work as a physicist had significant contributions to society.

Father Jaki wrote in his autobiography,

“I have always been very pleased to read books and learn.”

[10]

This is why, between 1951

and 1954, while he was already teaching, he decided to further his grasp of

physics

[11]

and attended courses in mathematics and physics,

obtaining a bachelor of science degree in physics in 1954.

[12]

However, on

December 9, 1953, his teaching career was interrupted. The “decisive factor”

was an extremely trivial event: the removal of his tonsils.

While this is usually a routine operation,

few days after surgery Father Jaki hemorrhaged in two spots

and was almost voiceless for the next ten years.

What little voice he had was insufficient for teaching,

but it did not prevent him from continuing his studies

and obtaining a PhD in Physics at the Fordham University in 1957.

[13]

Among his teachers was the 1936

Nobel Prize recipient in Physics, Victor Hess. A partnership arose between the

two, and Father Jaki conducted his research under Dr. Hess’ direction,

presented his dissertation in 1957, and published an article signed

by the two of them in the prestigious

Journal of Geophysical Research.

The thesis had as its title,

A study of the distribution of radon, thoron

(which are rare gases)

and their decay products above and below the ground.

[14]

Even if the title may seem rather abstruse,

radon is the second cause of lung cancer (after smoking).

His work as a physicist had significant contributions to society.

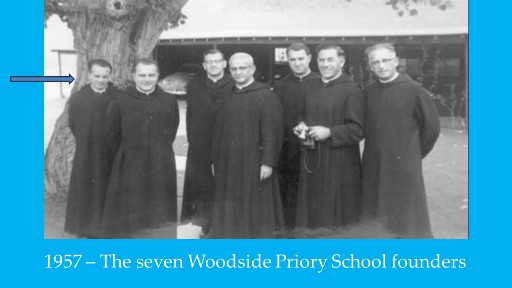

In that same year, 1957, Father Jaki was ordered to move to Portola Valley, in

California where with six other Hungarian Benedictines the Woodside Priory

School was founded. Since his voice was still absent, Father Jaki took care of

the administrative part of the school and continued his studies on the history

of science.

In that same year, 1957, Father Jaki was ordered to move to Portola Valley, in

California where with six other Hungarian Benedictines the Woodside Priory

School was founded. Since his voice was still absent, Father Jaki took care of

the administrative part of the school and continued his studies on the history

of science.

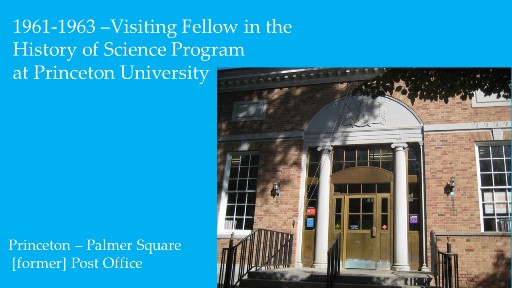

In 1960 Father Jaki moved back to the East Coast of the United States. At Princeton University,

between 1961 and 1963, he worked as Visiting Fellow on the History of Science

project.

There he took part to various graduate seminars in the history and philosophy of science.

[15]

And there he undertook

the research to write his first important work,

The Relevance of Physics.

[16]

Father Jaki recalls, “its idea

flashed through my mind as I walked down from the steps of Princeton’s Post

Office on Palmer Square”.

[17]

His doctoral thesis

was based on experiments and convinced Father Jaki that exact science has to

do with measurements and predictions. Accordingly, his definition of exact science

became “the quantitative study of the quantitative aspects of things in motion.”

[18]

Stated in Eddington’s

formulation, “the cleavage between the scientific and the extrascientific

domain of experience is, I believe, not a cleavage between the concrete and the

transcendental but between the metrical and the non-metrical.”

[19]

In practical terms, this means that the competence of physics is limited to the

measurable properties of everything, and in this sense science applies to

everything, but only to the measurable side of everything. For example, the

creation of the universe cannot be an object of science, but can only be dealt

with by philosophy and religion, since with science we can get as close as we

like to the moment of the Big Bang, but we cannot tell anything about what

caused it.

In 1960 Father Jaki moved back to the East Coast of the United States. At Princeton University,

between 1961 and 1963, he worked as Visiting Fellow on the History of Science

project.

There he took part to various graduate seminars in the history and philosophy of science.

[15]

And there he undertook

the research to write his first important work,

The Relevance of Physics.

[16]

Father Jaki recalls, “its idea

flashed through my mind as I walked down from the steps of Princeton’s Post

Office on Palmer Square”.

[17]

His doctoral thesis

was based on experiments and convinced Father Jaki that exact science has to

do with measurements and predictions. Accordingly, his definition of exact science

became “the quantitative study of the quantitative aspects of things in motion.”

[18]

Stated in Eddington’s

formulation, “the cleavage between the scientific and the extrascientific

domain of experience is, I believe, not a cleavage between the concrete and the

transcendental but between the metrical and the non-metrical.”

[19]

In practical terms, this means that the competence of physics is limited to the

measurable properties of everything, and in this sense science applies to

everything, but only to the measurable side of everything. For example, the

creation of the universe cannot be an object of science, but can only be dealt

with by philosophy and religion, since with science we can get as close as we

like to the moment of the Big Bang, but we cannot tell anything about what

caused it.

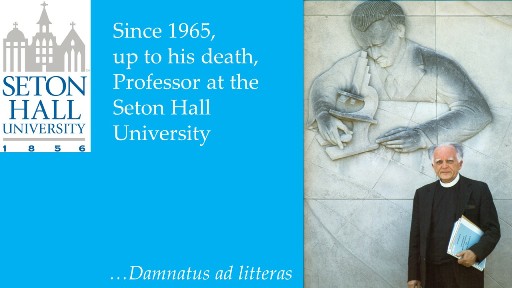

In 1965, before the publication of

The Relevance of Physics,

the dean of Seton Hall

University offered Father Jaki a post

as university professor, with an obligation to hold a weekly seminar,

and an unwritten obligation to continue writing.

Father Jaki defined his job as being

damnatus ad litteras,

i.e., condemned to write. With the permission of his

superiors, Father Jaki continued to live near Princeton,

commuting every week to Seton Hall,

to avail himself of the ancient books at the Princeton Libraries.

In 1965, before the publication of

The Relevance of Physics,

the dean of Seton Hall

University offered Father Jaki a post

as university professor, with an obligation to hold a weekly seminar,

and an unwritten obligation to continue writing.

Father Jaki defined his job as being

damnatus ad litteras,

i.e., condemned to write. With the permission of his

superiors, Father Jaki continued to live near Princeton,

commuting every week to Seton Hall,

to avail himself of the ancient books at the Princeton Libraries.

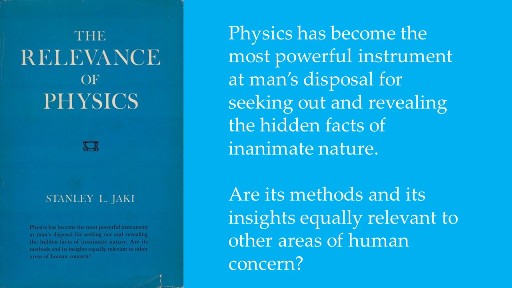

The cover of

The Relevance of Physics

reads: “Physics has become the most powerful

instrument at man’s disposal for seeking out and revealing the hidden facts of

inanimate nature. Are its methods and its insights equally relevant to other

areas of human concern?” The answer, of course, is negative, and Father Jaki

joked that the title should have been

The Irrelevance of Physics.

The book starts from an examination of the

three models of interpretation of the universe, the organismic one of the

ancient Greeks, the mechanistic one of Newton, and the contemporary one, based

on mathematics. The relationship of physics with biology, metaphysics, ethics

and theology are then examined.

The cover of

The Relevance of Physics

reads: “Physics has become the most powerful

instrument at man’s disposal for seeking out and revealing the hidden facts of

inanimate nature. Are its methods and its insights equally relevant to other

areas of human concern?” The answer, of course, is negative, and Father Jaki

joked that the title should have been

The Irrelevance of Physics.

The book starts from an examination of the

three models of interpretation of the universe, the organismic one of the

ancient Greeks, the mechanistic one of Newton, and the contemporary one, based

on mathematics. The relationship of physics with biology, metaphysics, ethics

and theology are then examined.

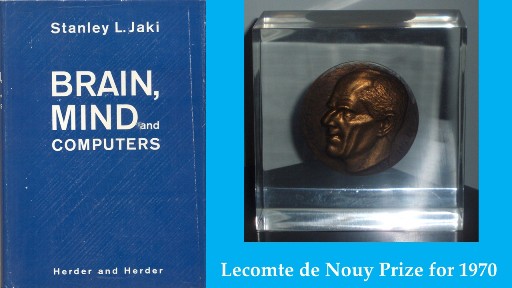

As a kind of continuation to

The Relevance of Physics,

Father Jaki wrote

Brain, Mind and Computers.

[20]

For that book he received

the Lecomte de Nouy prize in 1970. Father Jaki then wrote three books on the

history of astronomy, dealing respectively with Olbers’ paradox,

the Milky Way

and the formation of planets.

[21]

As a kind of continuation to

The Relevance of Physics,

Father Jaki wrote

Brain, Mind and Computers.

[20]

For that book he received

the Lecomte de Nouy prize in 1970. Father Jaki then wrote three books on the

history of astronomy, dealing respectively with Olbers’ paradox,

the Milky Way

and the formation of planets.

[21]

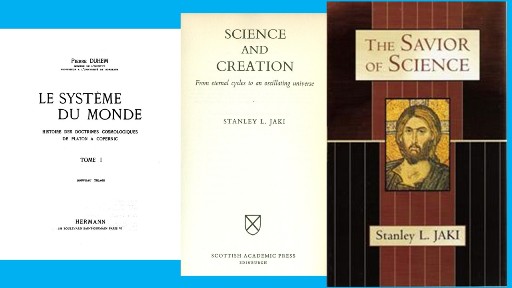

In the first decades of the 20th

century, the French scientist and

historian Pierre Duhem traced back the origin of modern Mechanics to the 14th

century University of Sorbonne, in Paris, specifically to the work of John

Buridan, in which one can find the first formulation of the Principle of

Inertia and, hence, the first of Newton’s Laws of motion.

[22]

Duhem’s main historical works are his ten volumes

Le système du monde.

[23]

Father

Jaki’s book

Science and Creation

deals with the reasons

for the stillbirths of science in each of all the main ancient cultures, and to

its only birth in medieval Christian Europe.

[24]

I will only mention here that all

ancient cultures had a cyclical view of time (“the great year”) which, as a

matter of fact, turns out to be “science-unfriendly.” Only the Judeo-Christian

culture has a linear view of time, that starts with God’s creation. In the book

The Savior of Science,

Father Jaki deals with the question: “Did

Christian belief have a part in the birth of science?”

If this is true, then Father Jaki argues that it is appropriate to then ask “Is

Jesus truly (also) the Savior of Science?” The book shows how both Judaism and

Islam failed to favor the birth of science, even though they had for five

centuries the monopoly of Aristotle’s books. This monopoly is important because

Buridan’s work that contains his theory of

impetus

is a commentary on Aristotle’s books on

Physics.

Christian faith

worshiped Christ, the only Begotten Son of the Father, in whom everything had

been created. Therefore, the universe was simply created (against the recurring

temptation of pantheism), and the universe had to be rational, as an expression

of a benevolent God. In the words of Father Jaki, “if the

Logos

was fully divine, its creative work [i.e., the universe] had to be the paragon

of logic and order.”

[25]

This observation has been

a powerful motivation for much research over the centuries. And in this sense

Jesus, seen as a guarantee of the rationality of the Universe, is the Savior of

Science.

In the first decades of the 20th

century, the French scientist and

historian Pierre Duhem traced back the origin of modern Mechanics to the 14th

century University of Sorbonne, in Paris, specifically to the work of John

Buridan, in which one can find the first formulation of the Principle of

Inertia and, hence, the first of Newton’s Laws of motion.

[22]

Duhem’s main historical works are his ten volumes

Le système du monde.

[23]

Father

Jaki’s book

Science and Creation

deals with the reasons

for the stillbirths of science in each of all the main ancient cultures, and to

its only birth in medieval Christian Europe.

[24]

I will only mention here that all

ancient cultures had a cyclical view of time (“the great year”) which, as a

matter of fact, turns out to be “science-unfriendly.” Only the Judeo-Christian

culture has a linear view of time, that starts with God’s creation. In the book

The Savior of Science,

Father Jaki deals with the question: “Did

Christian belief have a part in the birth of science?”

If this is true, then Father Jaki argues that it is appropriate to then ask “Is

Jesus truly (also) the Savior of Science?” The book shows how both Judaism and

Islam failed to favor the birth of science, even though they had for five

centuries the monopoly of Aristotle’s books. This monopoly is important because

Buridan’s work that contains his theory of

impetus

is a commentary on Aristotle’s books on

Physics.

Christian faith

worshiped Christ, the only Begotten Son of the Father, in whom everything had

been created. Therefore, the universe was simply created (against the recurring

temptation of pantheism), and the universe had to be rational, as an expression

of a benevolent God. In the words of Father Jaki, “if the

Logos

was fully divine, its creative work [i.e., the universe] had to be the paragon

of logic and order.”

[25]

This observation has been

a powerful motivation for much research over the centuries. And in this sense

Jesus, seen as a guarantee of the rationality of the Universe, is the Savior of

Science.

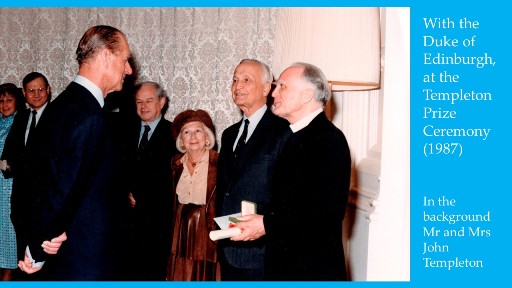

Alfred Nobel (1833-1896), the originator of the Nobel Prizes,

despite being nominally a Lutheran was not particularly religious. For this

reason, among the Nobel Prizes there is no prize linked to religion, even if

peace prizes have occasionally been awarded to religious personalities. To fill

this gap, John Marks Templeton (1912-2008), an American-English businessman and

philanthropist, established an award in 1972 that bears his name, “for

progress in religion”. Father Jaki received the award in 1987. The motivation

reads: “It is above all for his immense contribution to bridging the gap

between science and religion, and his making room in the midst of the most

advanced modern science for deep and genuine faith, that he received the

Templeton Prize.”

[26]

Alfred Nobel (1833-1896), the originator of the Nobel Prizes,

despite being nominally a Lutheran was not particularly religious. For this

reason, among the Nobel Prizes there is no prize linked to religion, even if

peace prizes have occasionally been awarded to religious personalities. To fill

this gap, John Marks Templeton (1912-2008), an American-English businessman and

philanthropist, established an award in 1972 that bears his name, “for

progress in religion”. Father Jaki received the award in 1987. The motivation

reads: “It is above all for his immense contribution to bridging the gap

between science and religion, and his making room in the midst of the most

advanced modern science for deep and genuine faith, that he received the

Templeton Prize.”

[26]

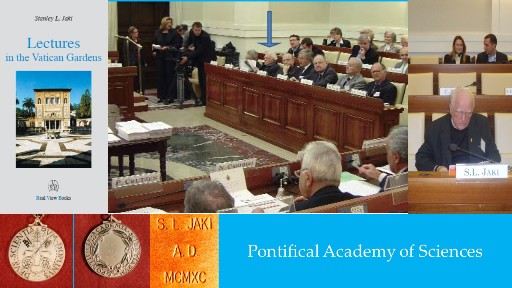

In 1990 Father Jaki was invited to join the Pontifical Academy of

Sciences as an Honorary Member (i.e., as a member not directly involved in

scientific research). All the talks of Father Jaki to the Pontifical Academy of

Sciences were published posthumously in 2011 under the title

Lectures in the Vatican Gardens.

[27]

In 1990 Father Jaki was invited to join the Pontifical Academy of

Sciences as an Honorary Member (i.e., as a member not directly involved in

scientific research). All the talks of Father Jaki to the Pontifical Academy of

Sciences were published posthumously in 2011 under the title

Lectures in the Vatican Gardens.

[27]

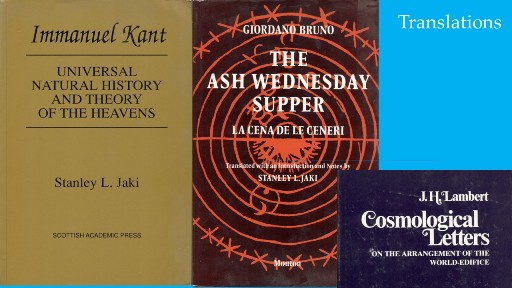

Father Jaki translated into English three philosophical works: the early

work of Kant,

Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens,

Giordano Bruno’s

The Ash Wednesday Supper,

and Lambert’s

Cosmological Letters.

[28]

He did so to demonstrate how ideas

a priori

could easily bring an author

far from truth. Just as an example, the image of the universe that emerges from

Lambert’s speculations, even if contains a number of very interesting ideas,

overstates the role of comets and abuses (as Kant does) of the then common

conviction that all planets and comets

were inhabited.

Father Jaki translated into English three philosophical works: the early

work of Kant,

Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens,

Giordano Bruno’s

The Ash Wednesday Supper,

and Lambert’s

Cosmological Letters.

[28]

He did so to demonstrate how ideas

a priori

could easily bring an author

far from truth. Just as an example, the image of the universe that emerges from

Lambert’s speculations, even if contains a number of very interesting ideas,

overstates the role of comets and abuses (as Kant does) of the then common

conviction that all planets and comets

were inhabited.

Father Jaki wrote a number of books as a theologian. We can recall

the ones to defend the Papacy, the ones about the Bible, in particular about

the first Chapter of the Book of Genesis and the ones about miracles.

[29]

Father Jaki wrote a number of books as a theologian. We can recall

the ones to defend the Papacy, the ones about the Bible, in particular about

the first Chapter of the Book of Genesis and the ones about miracles.

[29]

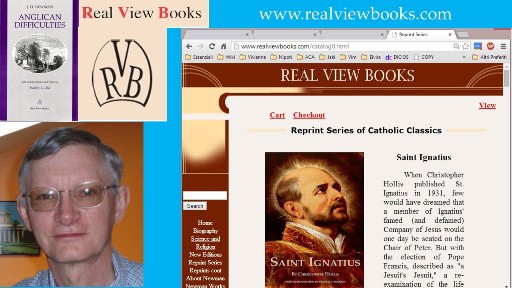

Father Jaki founded a non-profit publishing house, Real View Books,

which started publishing works no longer in print, like Newman’s

Difficulties of Anglicans,

and a number of books written by Father Jaki himself.

[30]

After Father Jaki’s death,

Real View Books completed the publication of works he

left “ready for print” and continues to reprint his books as needed. For

example, a new edition of

Science and Creation

came out in 2016. The

number of items in Father Jaki’s publication list is well over 700. About 100

books and booklets he wrote are available from Real View Books. The soul of the

Real View Books publishing house is Dennis Musk.

Father Jaki founded a non-profit publishing house, Real View Books,

which started publishing works no longer in print, like Newman’s

Difficulties of Anglicans,

and a number of books written by Father Jaki himself.

[30]

After Father Jaki’s death,

Real View Books completed the publication of works he

left “ready for print” and continues to reprint his books as needed. For

example, a new edition of

Science and Creation

came out in 2016. The

number of items in Father Jaki’s publication list is well over 700. About 100

books and booklets he wrote are available from Real View Books. The soul of the

Real View Books publishing house is Dennis Musk.

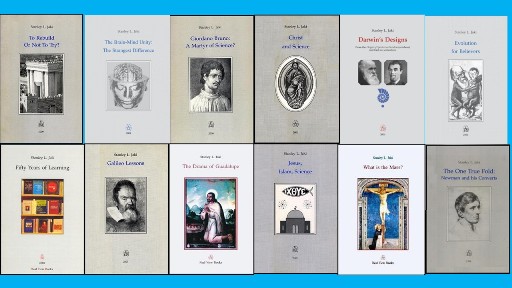

Father Jaki also wrote several 32-pages booklets, which are short

version of longer works or monographies. For example,

Christ and Science

is a short version of

The Savior of Science.

Father Jaki also wrote several 32-pages booklets, which are short

version of longer works or monographies. For example,

Christ and Science

is a short version of

The Savior of Science.

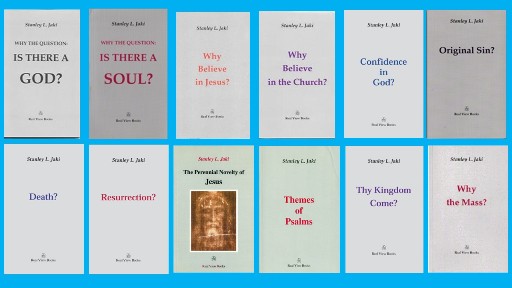

A series of short books (about 80 pages each) deals with the basic

topics of theology. They constitute a short compendium of apologetics. Father

Jaki had in plan a book on the subject,

Apologetics in an Age of Science,

but he died before writing it.

What is left in his papers is a folder (found by the present writer) with a few

preparatory pages, including the titles of the chapters and a possible cover.

Father Jaki had an exchange of messages about this book with John Beaumont, who

wrote a paper on the matter.

[31]

A series of short books (about 80 pages each) deals with the basic

topics of theology. They constitute a short compendium of apologetics. Father

Jaki had in plan a book on the subject,

Apologetics in an Age of Science,

but he died before writing it.

What is left in his papers is a folder (found by the present writer) with a few

preparatory pages, including the titles of the chapters and a possible cover.

Father Jaki had an exchange of messages about this book with John Beaumont, who

wrote a paper on the matter.

[31]

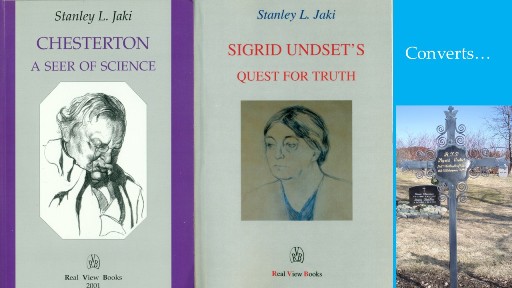

Father Jaki paid particular attention to converts, because they often

demonstrate in their new faith a livelier intellectual acumen and apologetic

than “cradle Catholics.” One of Father Jaki’s favorite authors was in fact a

convert, Gilbert Keith Chesterton. Father Jaki dedicated several articles to

him, and one book,

Chesterton, a Seer of Science,

that is, a visionary regarding science.

[32]

Let’s remember that Chesterton was anything but tender with the scientism

that dominated his era.

Father Jaki’s research on the conversion of

Sigrid Undset was a particularly laborious undertaking, which also required the

translation for the first time of some of Undset’s texts from Norwegian

into English. Father Jaki also visited the places where Sigrid Undset lived,

while researching this book.

[33]

Father Jaki paid particular attention to converts, because they often

demonstrate in their new faith a livelier intellectual acumen and apologetic

than “cradle Catholics.” One of Father Jaki’s favorite authors was in fact a

convert, Gilbert Keith Chesterton. Father Jaki dedicated several articles to

him, and one book,

Chesterton, a Seer of Science,

that is, a visionary regarding science.

[32]

Let’s remember that Chesterton was anything but tender with the scientism

that dominated his era.

Father Jaki’s research on the conversion of

Sigrid Undset was a particularly laborious undertaking, which also required the

translation for the first time of some of Undset’s texts from Norwegian

into English. Father Jaki also visited the places where Sigrid Undset lived,

while researching this book.

[33]

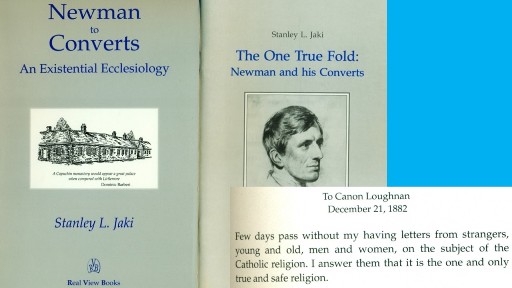

But the convert with whom Father Jaki spent the most time is

undoubtedly Saint John Henry Newman, the most illustrious convert of the XIX

century, whom Father Jaki had quoted in his writings since his 1950 thesis. Father Jaki

dedicated several books and dozens of articles and conferences to Newman, and

he also had some of Newman’s works reprinted. One of his concerns was not to

let Newman be transformed into the precursor of an ecumenism, very popular

after the Second Vatican Council, which tended to minimize the doctrinal

differences with the Protestants. Perhaps Father Jaki’s most significant work

on the subject is the book

Newman to Converts: An Existential Ecclesiology,

the result of meticulous research carried out in Birmingham in Newman’s own library.

In this book, Father Jaki traces the events that led to the conversion of around

twenty people from Anglicanism to Catholicism,

deriving the material from the volumes of Newman’s

Letters and Diaries

and from documentation of the time.

[34]

The advice that Newman gave can be summed up in one of the sentences at the beginning of

the book: “Not many days go by without my receiving letters from strangers,

young and old, men and women, regarding the Catholic religion. I reply to them

that it is the one and only true and certain religion.”

[35]

A short version of the

book appeared before the book itself, titled

The One True Fold: Newman and His Converts.

[36]

But the convert with whom Father Jaki spent the most time is

undoubtedly Saint John Henry Newman, the most illustrious convert of the XIX

century, whom Father Jaki had quoted in his writings since his 1950 thesis. Father Jaki

dedicated several books and dozens of articles and conferences to Newman, and

he also had some of Newman’s works reprinted. One of his concerns was not to

let Newman be transformed into the precursor of an ecumenism, very popular

after the Second Vatican Council, which tended to minimize the doctrinal

differences with the Protestants. Perhaps Father Jaki’s most significant work

on the subject is the book

Newman to Converts: An Existential Ecclesiology,

the result of meticulous research carried out in Birmingham in Newman’s own library.

In this book, Father Jaki traces the events that led to the conversion of around

twenty people from Anglicanism to Catholicism,

deriving the material from the volumes of Newman’s

Letters and Diaries

and from documentation of the time.

[34]

The advice that Newman gave can be summed up in one of the sentences at the beginning of

the book: “Not many days go by without my receiving letters from strangers,

young and old, men and women, regarding the Catholic religion. I reply to them

that it is the one and only true and certain religion.”

[35]

A short version of the

book appeared before the book itself, titled

The One True Fold: Newman and His Converts.

[36]

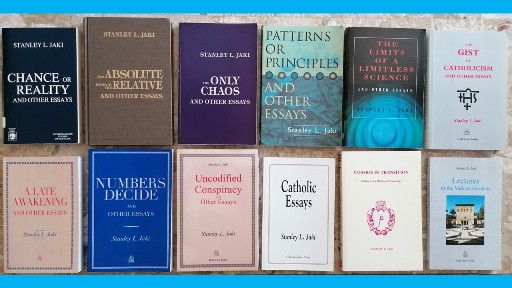

Among Father Jaki’s interventions there are articles for magazines

or conferences at universities. Many of these texts have been collected in book

form, with the first essay giving the book its title, followed by

“and Other Essays.”

[37]

Among Father Jaki’s interventions there are articles for magazines

or conferences at universities. Many of these texts have been collected in book

form, with the first essay giving the book its title, followed by

“and Other Essays.”

[37]

Regarding Father Jaki and his vocation, since he was a child he

wanted to become a priest, and this undoubtedly happened. Without the ruthless

persecution carried out by communism in Hungary, he would never have been sent

to America. Without the consequences of a banal removal of his tonsils he would

never have gone from teaching to a career as a writer. Many other events in his

life as a writer (and maybe in our own life)

depended on seemingly random (or providential) encounters.

Father Jaki liked the Portuguese proverb “God writes straight along (our) crooked lines”.

[38]

Finally, it

seems appropriate to quote a further few lines from his intellectual autobiography,

A Mind’s Matter.

[39]

Regarding Father Jaki and his vocation, since he was a child he

wanted to become a priest, and this undoubtedly happened. Without the ruthless

persecution carried out by communism in Hungary, he would never have been sent

to America. Without the consequences of a banal removal of his tonsils he would

never have gone from teaching to a career as a writer. Many other events in his

life as a writer (and maybe in our own life)

depended on seemingly random (or providential) encounters.

Father Jaki liked the Portuguese proverb “God writes straight along (our) crooked lines”.

[38]

Finally, it

seems appropriate to quote a further few lines from his intellectual autobiography,

A Mind’s Matter.

[39]

[Before seeing things

sub species aeternitatis]

one must feel satisfied with the fact that

militia est vita hominis super terram

(on this earth man’s life

is a military service) (Job 7:1), to recall from the Vulgate a sober reflection of the

much tried Job. Our soldiering must go on, with the phrase “Only a few good

marines are needed” in our focus, a phrase which summarizes a truly existential

theology. The phrase also conveys the theological equivalent of a mere private,

which is the rank of a useless servant, who merely does his duty. May this

remain the matter foremost in my mind.

This book is also very useful for understanding Father Jaki’s intellectual itinerary. Another biblical phrase that Father Jaki loved to quote is: “Even to the death fight for truth, and the LORD your God will battle for you” (Sir 4:28).

Father Jaki’s website

(http://www.sljaki.com)

contains much information

about Father Jaki, and an updated list of his publications. A group of Father

Jaki’s friends is known as the “Stanley Brigade,” a name chosen by

Father Jaki himself. The group is informal. To join it, one can

write an email to stanley.brigade@gmail.com.