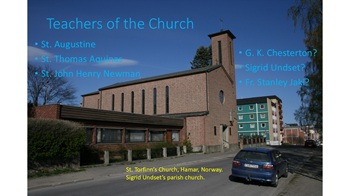

Three Catholic Intellectual Giants

by Geir Hasnes, M.S.

1. Anniversaries and centenaries of G. K. Chesterton, Sigrid Undset and Fr. Stanley Jaki

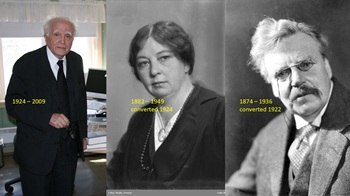

On May 29 this year [2024], we celebrate G. K. Chesterton’s 150th anniversary, and on August 17, we celebrate Father Stanley Jaki’s centenary. In between them, on June 10, we remind ourselves that 75 years have passed since Sigrid Undset passed away, and on November 1, we celebrate the centenary of her conversion.

2. The relationship between the three authors

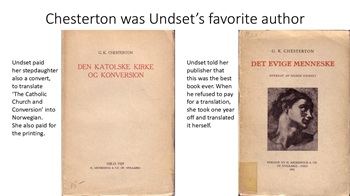

Most Chesterton biographies do not mention Sigrid Undset, the Norwegian Nobel prize winning novelist, and if they do so, it is only in passing. Her Norwegian biographers, though, mentions Chesterton casually, because she called him her favorite author and used to read aloud from his books to friends and family. She probably discovered him in 1912 when she spent six months in England after she had married. She became increasingly interested in him after that, to the point that she even translated The Everlasting Man into Norwegian in 19311.

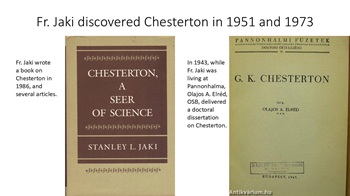

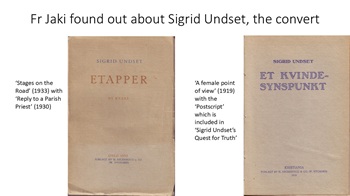

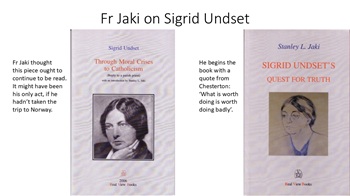

Father Jaki discovered Chesterton in 1951, but did not take him in until 1973, when, as he wrote: ‘Chesterton started acting on me as an irresistible magnet’.2 Subsequently he wrote a monograph3 and several articles on him. Late in life he also discovered Undset, and became intensely interested in her life and work, to the point that he wrote one of his last books on her.4

Why string these three authors together in this paper? The anniversaries seem to be a good enough reason to focus both on Undset’s and Fr Jaki’s interest in Chesterton and Fr Jaki’s interest in Undset. Too little has been written on the relationship between Undset and Chesterton and almost nothing about Fr Jaki’s relationship to Chesterton and Undset.

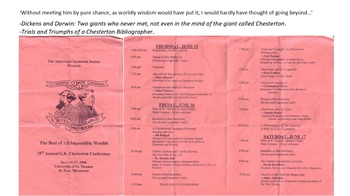

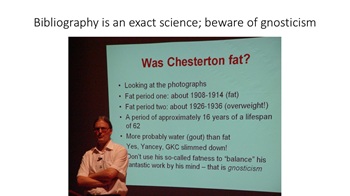

My personal interest in the relationship between those three is founded in my lifelong interest in G. K. Chesterton and Sigrid Undset. In 2022, my bibliography on G. K. Chesterton was published.5 When I attended the American Chesterton Society’s annual Chesterton conference in 2006 to speak on my bibliographical work, I met with Fr Jaki. It turned out that he had recently taken an interest in my fellow Norwegian Undset, and I offered to help him if he wished to go to Norway to do more research on her. He took up the offer, and I drove him twice to Undset’s residence in Lillehammer, now a museum. Not only did these trips help Fr Jaki’s research, but they also added him to my list of authors I need to collect all of.

[Geir Hasnes and Stanley Jaki at the Chesterton Conference, St. Paul, Minnesota, 15-17 June 2006]

[Lillehammer, Bierkebaek, House of Sigrid Undset]

[Bierkebaek, Geir Hasnes and Stanley Jaki at the house of Sigrid Undset]

[Geir Hasnes and Stanley Jaki at the Tomb of Sigrid Undset]

3. The differences

Although Chesterton, Undset and Fr Jaki were both Catholics and authors, they were surprisingly different in several ways.

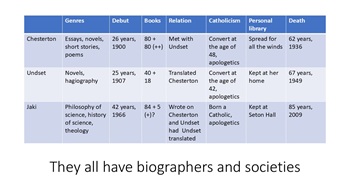

3.1 Genre

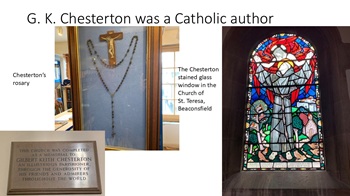

Chesterton was first and foremost a journalist, who also happened to write books. He wrote regularly for large newspapers and magazines, was immensely prolific and had about eighty books published in his lifetime and a lot of collections of unpublished material appearing later. He may have written (or rather, dictated) five – six thousand essays, more than one thousand poems, more than one hundred short stories, and most of his books were put together from these.6 He was also a revered public speaker, and may have delivered more than one thousand public speeches, lectures, or participated in public debates, and a majority of these are recorded, several in full and more than half in part.7 One may best characterize Chesterton as an essayist, and his books often seem to be enlarged essays. He was no journalist in today’s sense of the word; he decided himself what to write about.

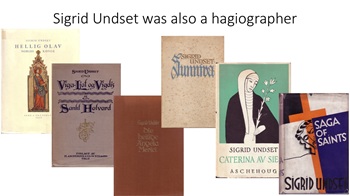

Sigrid Undset was first and foremost a novelist. She had more than forty books published in her lifetime and many works of different kinds after her death. She wrote hundreds of articles, but was not by any means as prolific as Chesterton. She was a typical novelist and from her debut onwards she soon was able to live from her sales. However, she also adapted and translated several Catholic books into Norwegian.

Father Stanley Jaki was a Hungarian born Benedictine priest who at the age of about forty was employed as a professor at Seton Hall university. He had two doctorates in theology and physics and wrote mainly books and articles on science, the history of science, and theology. Many of his books consists of lectures, and there is overall an oral delivery in his texts. He had at least eighty books published in his lifetime and since then many collections have arrived.

3.2 Debut

Chesterton made his debut at 26 in 1900, Undset at 25 in 1907, and if we exclude Fr Jaki’s doctoral dissertation in 1957, he made his debut 42 years old in 1966 with The Relevance of Physics.8 We know that both Chesterton and Undset wrote extensively from their teenage years onwards, and both were employed, Chesterton as a manuscript reader and ghost writer in publishing companies and Undset as a secretary, until they were able to live by their pens. Fr Jaki was an ordained priest who continued studying for several years and who was also employed as a teacher. A tonsillectomy made him concentrate further on studies and finally he found his vocation as an author on science and religion.

3.3 Use of sources and libraries

Chesterton had a remarkable memory and did not use libraries, except from when he was working on his life of Robert Browning. He also quoted from memory and was famous for making up lines in other people’s poems; Chesterton insisted on quoting from memory because he viewed the effect the poem had on the reader as important, even if that meant that the poem would not come out as originally written.9

To the opposite, Undset and Fr Jaki both researched thoroughly everything that was treated in their books. Undset’s father was an archaeologist and Undset took an interest in history from her earliest years. Before writing her medieval masterpieces in the 1920s, she was theoretically well founded both in Norwegian history and in Catholic theology. Fr Jaki, then, spent several decades diving deep into Catholic theology and science before he began publishing his studies.

Chesterton owned a huge collection of books which today has been scattered to the winds. Nobody really knows how large his library was. Already, in his late teens he must have read tremendously, and it may seem that the family had a huge library. He doesn’t seem to have collected literature at all; he used to buy whichever book appealed to him at the instant, and he must have been sent a multitude of books to review during his life. A research project ought to be started on his knowledge of literature.

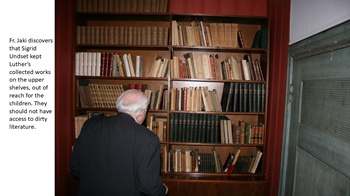

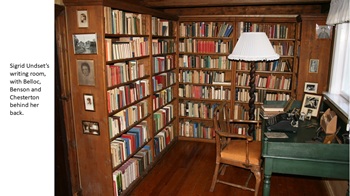

On the other hand, Undset built her collection of books consciously from the start, spending a lot of her income on books, while also receiving a torrent of books from publishers and friends. Her library numbered about 5,000 books at the outbreak of World War II, and after she had fled from the German occupiers, her library was hidden by friends in church crypts in the area. She brought with her about 4,000 books from the United States after the war, and at her death the library numbered 10,300 books. 1300 of them, her collection of old Norse literature, were willed to a library in Trondheim, and the rest of it stayed untouched, gathering dust for 48 years until the estate was bought and made into a museum. Her whole library has been catalogued and is available for research. 10

Fr Jaki also built up a personal library during his life, and he also visited the libraries nearby for his work, for instance at Stanford University and especially at Princeton University.11 Luckily, he had dedicated helpers, who could empty his flat after his death, keep his personal computer and make backup of everything, and make a catalogue of the inventory before it was sent to Seton Hall.

When Fr Jaki died, his library was sent directly to Seton Hall. His papers and the books he wrote were sent to New Hope (Real View Books). I went through them, “built” a “physical” Publication List, which is still in New Hope, in some 12 boxes or so, with a few other items, but most of the stuff, letters, books, xeroxes, folders in preparation of books etc. (including some original Duhem material) were sent to Seton Hall... Fr Jaki left all the rights to his books to Real View Books.12

3.4 Death and health

Chesterton died at 62, Undset at 67 and Fr Jaki at 84. When Fr Jaki had reached 62 he had ‘only’ published about seventeen books, and in his last three decades he wrote with a tremendous speed until his passing.

Chesterton died prematurely from smoking too much. He was a chain-smoker and did not take much care of his health, which probably was a reaction to his father being a hypochondriac. Undset also died from smoking too much; she used to write in the evenings out into the night after the children had gone to bed, and was chain-smoking while she wrote. She also felt very tired during her last years, as she had fled to the United States from the Germans in 1940, and acted as an ambassador for Norway there during World War II. Fr Jaki was in this respect the opposite of the other two, he was a healthy and dynamic person full of energy and vitality to the end.

Chesterton and Undset were thus children of their time, when people used to smoke everywhere. It is sad to think of how much more they could have written as everything they published was of such a high quality. Very few authors deserve that everything they have written is available for the public. All these three intellectual giants deserve to have their intellectual legacy taken care of.

3.5 Biographers

One may wonder how Undset may have corrected our view of Chesterton if she had written his biography, as most of his biographers either were not Catholics or they misread him or hadn’t researched him well. Only two biographers were able to penetrate deep into Chesterton’s mind; William Oddie13 and Fr. Ian Ker14, both Catholics. Oddie, though, only covered Chesterton’s life up to 1908 and the publication of Orthodoxy.

Now it may be unfair to ask of any biographer that he should be able to grasp the enormous mind of Chesterton. Not only is there more than enough material, but there is also a huge amount of controversy as Chesterton took an active part in the debates of the day. A biographer must choose what is important and what is not so important in the life of that person. This filtering process is based upon the worldview of the biographer.

The definitive biography of Sigrid Undset still remains to be written. Just as with Chesterton, most biographers view her life as ‘before and after conversion’. Secular biographers tend to prioritize the ‘before’ part, while Catholic biographers tend to diminish her conservative and uncompromising Catholicism. Norway was in her time a Lutheran and largely anti-Catholic country and is now a very secular country, taking little interest in organized religion at all. Undset also took an active part in the debates of the day, although not being such a vigilant voice as Chesterton. One of the reasons is, of course, that Chesterton lived in the middle of the world of the news in those days, while Undset lived on the outskirts of a country on the outskirts of the world. Chesterton had a smooth machinery around him, from secretaries to literally hundreds of newspapers and magazines only too eager to print whatever he tossed off. Undset had no secretary, and she had her outlets, but most of her controversies were, in the more positive meaning of the word, provincial. What Norwegians were arguing against each other in those days did not reach far outside their borders.

Books on Fr Jaki have already appeared, but no definitive biography among them. The difference between Fr Jaki, on the one hand, and Chesterton and Sigrid Undset, on the other, is that the latter two built up a huge readership before they became converts, and most of their literary production appeal to people of most creeds or lack of it. Fr Jaki was exclusively Catholic in all his writings. One might argue that science is not exclusively Catholic and that Fr Jaki should appeal to anyone with an interest in the philosophy of science. One may not be so sure about that. Books about science always comes with a taint of religion, of dogmatism, of prejudice, of philosophical preferences. Some may for instance defend Giordano Bruno as an important person for science. Fr Jaki said that he had to translate a work of Bruno so that he could grasp how little Bruno knew about science. This is both a good anecdote and an indicator of how easy it is to build a controversy out of seemingly non-controversial material.

Books about Fr Jaki tend to focus on his written material more than on his personal life. One could probably write a huge tome on Chesterton only quoting anecdotes and humorous stories about him, as he was a huge public figure, a landmark, and as an outspoken defender of the poor and attacker of the unjust, with an aptitude for epigrams. There is probably also a large number of anecdotes about Fr Jaki floating about, judging from his obituary alone, but not many of them have been written down.

While Chesterton was a public figure, speaking with everyone everywhere, Undset was not found of speaking to people she didn’t know, to the point of being rude and dismissive even to fans. She was courteous to her friends, fellow authors and fellow Catholics, but did not deliver witty answers to her opponents for instance in debates the way Chesterton always crushed his opponents with some humorous and pointed remark. Fr Jaki was quick the way Chesterton was, and my impression is that he must have been very interesting to listen to in a debate, and probably quite annoying to the other point of view.

Compared to Chesterton and Undset, Fr Jaki doesn’t have the same amount of biographical detail to delve into; he was largely ‘condemned to sit at home and write’ – and therefore, his biographers will mainly look into what he wrote, and therefore even become tempted to write their own treatises instead of writing a proper ‘life’ of him. Biographers of Chesterton tend to become hagiographers and therefore make up something to criticize along the way, biographers of Undset tend to misunderstand or dismiss her conservative Catholicism, and biographers of Fr Jaki must avoid being hagiographers or ‘system builders’.

3.6 Societies

Chesterton has got his Chesterton Society, founded at his centenary in 1974, and the Chesterton Review , founded the same year. There is also a ferocious America Chesterton Society arranging conferences and publishing a bi-monthly magazine [Gilbert!] and books on Chesterton every now and then, and there are smaller Chesterton societies in many other countries. Sigrid Undset has also got her society in Norway, where the State, together with the local museum, bought her estate and belongings and turned it into a separate institution, complete with a new exhibition building erected at the centenary of her debut. The Stanley Jaki Foundation and the recently founded Stanley Jaki Society keep up the legacy of Fr Jaki with books and conferences.

4. The similarities

Gilbert and Frances Chesterton married in 1901, and they had no children. His sister-in-law Ada Chesterton wrote about the pair that the marriage had not been consummated. The statement has since been thoroughly rejected by almost all Chestertonians, but there is reason to believe that there is something to it. We know that Frances had an operation in order to have children, and that it failed. We also know that Gilbert Chesterton never spoke about his private life and any letters or papers deemed too personal were destroyed after his death. Frances also had a fragile health and was regularly ill. After they had married, Gilbert put on weight and drank too much; and there is reason to believe that if they had regular intercourse, it would not have lasted for more than a few years.

However, when Chesterton was asked about how it could be that he could write so much and know so much, he referred to the necessity of being chaste.

Sigrid Undset was fond of men, even of older men, and she had affairs even with married men before she met Anders Svarstad, whom she married after he had divorced his first wife.

During the next years, Undset began to develop an interest in Catholicism, and it dawned upon her that from a Catholic viewpoint, she was not properly married as Svarstad’s first wife still was alive. She also moved to inland Norway in order to find a better environment for her work as an author, and Svarstad did not want to move with her. Then, in order to convert to Catholicism, she simply divorced Svarstad and never remarried. When asked about how it felt to live without a man, she replied that it was not any worse than living with only one man.

Undset, then, also lived a chaste life. So also with Fr Jaki, who as a priest lived in celibacy. Chastity produces incredible insights.

5. Undset and Chesterton

Undset’s biographers used to say that Chesterton and Belloc were crucial to her conversion. Luckily, her library became available to researchers after 2007, and even better, Undset used to write the date of purchase in the books. By that, to put it short, one finds that Undset was fascinated by the saints and martyrs of the church; it is fair to assume that those were among the main reasons for her to study Catholicism, and the only book Chesterton had written on Christian themes until then was Orthodoxy, which she read in 1920. One of the biggest influences must have been Robert Hugh Benson; she read his novels during 1917 and 1918. She took a public standpoint for Christianity in 1919 and converted in 1924. She then translated two books by Benson in 1926 and 1928, showing an interest in Christian mysticism which has not been understood by any of her biographers..

On May 7, 1928, Sigrid Undset wrote to Chesterton from Wilton Hotel, Victoria, S.W.1:15

G. K. Chesterton Esq.

Dear Sir!

Although I know that your time is very much occupied I take the liberty to beg an interview with you, as the Dominican fathers of Oslo wanted me to call on you. I am a catholic from Norway, over here principally to see something of the work the English Catholics do and see if I can learn something that might come in usefully for our own work at home.

Please would you let me have a word, if, and when I might meet you.

Yours respectfully

Sigrid Undset

She enclosed her visiting card. On the letter is noted: Acknowledged / Will write later.

Then, on May 25, Sigrid Undset indeed visited Chesterton at his home in Beaconsfield16. We know nothing about the meeting, but we know what came out of it. In her papers, we can find a deal struck with Macmillan for rights to translating various books by Belloc, Chesterton etc. for the fee of $500, which meant books in Macmillan’s series on the Catholic Church, edited by Hilaire Belloc.17

In December 1929, two books from the series appeared: The Catholic Church and Conversion by Chesterton, translated by Undset’s stepdaughter Ebba Svarstad18, and The Catholic Church and History, translated by Undset’s friend Ellen Faaberg19. What is not commonly known is that Sigrid Undset paid for the publication of the two books out of her own pocket. Her Norwegian publisher may not have agreed that the translations were worthwhile. While Undset certainly wished to get more books from the series published, it began and ended with these two books.

However, Undset was not through with bringing the English Catholics to Norway. After having completed her two-volume novel describing the conversion process in 1930, she took a year off to translate Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man in 1931. She had already written several biographies of Norwegian saints, and they all ended up in Saga of Saints, which was published in 1934 in Sheed and Ward’s series of books on saints, where, for instance, both Chesterton, Belloc and Christopher Dawson had contributed to The English Way the year before.20 She continued to write several biographies of European saints, but about 1935, the tide had waned and little more should come out of the cooperation between her and Chesterton and his co-Catholics.

6. Fr Jaki and Chesterton

What struck me most with Fr Jaki was his constant hunger for knowledge combined with the instant treatment of this knowledge when it was acquired, this wish to do something instantly with what he took an interest in. I can understand that he was seen as demanding by some, and polemical by others. I think he was just as demanding to himself; the wish to learn and to build a system out of what he learnt was a driving force in him, if not the main driving force. He was impatient with others inasmuch he was impatient with himself. For such a person, it is hard to take an interest in most people, because they don’t bring anything he doesn’t know and would not have thought through already.

When Fr Jaki discovered Chesterton, however, he found a person whose mind had seen the same things as he had, and perhaps put them in writing noticeably more eloquently than him. His book tells us about Chesterton’s “sparkling gems”, that he spoke “very attractively”; indeed, Fr Jaki had found somebody to marvel about.21 Not only that, but as opposed to a lot of philosophers and scientists Fr Jaki admired, Chesterton also had the same foundation in the Faith and thought the same thoughts as Fr Jaki. In short, “the Universe had few finer champions than Gilbert Keith Chesterton”.

7. Fr Jaki and Sigrid Undset

When I first met Fr Jaki at the Chesterton conference back in 2006, he was so noticeably attentive. At the lunch table, when he heard that I came from Norway, he didn’t hesitate, but straight on asked me to tell him about Sigrid Undset. There was no presentation either; he just jumped into it, and, I think to his appreciation, I just went on and on – and he drank it in. Because he told me that he had been looking into Undset and was working on a translation of a central text of hers,22 it struck me that he ought to go to Norway to do research – and of course it would be easy for me to help him with that. It was nothing more to it than that; I wasn’t sure whether he would pick up the offer, but he did, and that ended up with a book full of appreciation for yet another soulmate of his.

Indeed, he appreciated Sigrid Undset so much that when I sent an article on the relationship of the two to the Chesterton Review, I entitled it “Father Stanley Jaki and Sigrid Undset: A Love Story”.23 However, I think the editor found it too flippant, but I meant what I said: Just as I love Chesterton’s, Undset’s and Fr Jaki’s writings, I think Fr Jaki found yet another person to love in the meaning of admiring her mind and actions.

In the book that followed, Fr Jaki discussed various books and articles on Undset, and dissected them in his usual polemical style, showing how they were missing a point or three. It is a delight to read, also because Fr Jaki is so eloquent himself. How better to state it than to say that “truth in its finest form was for Sigrid Undset to live in a deeply personal friendship with Christ as regulated by the only Church He founded.”24

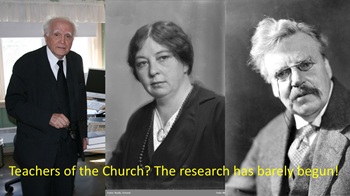

Conclusion. The teachers of the Church

This short essay can only scratch the surface of the relationship between these intellectual and Catholic giants. They were not much alike with regard to lifestyle and personality, but they had their Faith and their incredible ability to write convincingly in common. Fr. Jaki discovered both of them and wrote books about them, and for anyone taking an interest in Fr. Jaki, I am convinced that taking an interest in Chesterton and Undset will be richly rewarding.

In G. K. Chesterton, Sigrid Undset and Fr Stanley Jaki, we have acquired yet three teachers of the Church. Now that we celebrate their anniversaries and the conversions of two of them, may the Church recognize them as that and treat them accordingly.

1 G. K. Chesterton: Det evige menneske, translated by Sigrid Undset (Oslo: H. Aschehoug), 1931: https://www.nb.no/items/13639e5a16d3346c178f797853b6cec3.

2 Stanley L. Jaki: Chesterton, a Seer of Science (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press), 1986, p. ix.

3 Stanley L. Jaki: Chesterton, a Seer of Science (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press), 1986.

4 Stanley L. Jaki: Sigrid Undset’s Quest for Truth (Port Huron: Real View Books), 2007.

5 Geir Hasnes: G.K. Chesterton. A Bibliography (Kongsberg: Classica), 2022. Three volumes.

6 Hasnes: G.K. Chesterton. A Bibliography.

7 Geir Hasnes: “Chesterton as Public Speaker”, The Chesterton Review 47 (1-2), 2021, pp. 63-75. https://doi.org/10.5840/chesterton2021473/470

8 Stanley L. Jaki: The Relevance of Physics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), 1966.

9 As a result, several of Chesterton’s books had new impressions corrected, notably Robert Browning (1903) and The Victorian Age in Literature (1913).

10 Geir Hasnes: “Sigrid Undset i bøkenes verden”, Gymnadenia Årsskrift (Lillehammer: Sigrid Undset-selskapet), 2008, 6 unpaginated pages, in Norwegian. See also Geir Hasnes: “Sigrid Undset and the Saints”, StAR. Saint Austin Review 21 (6), 2021 (Houston: The Center for Cultural Renewal), pp. 4-7.

11 Antonio Colombo: From Győr to Madrid, http://www.sljaki.com/biographies/america-colombo.html, 2018 and later.

12 Antonio Colombo, email to the author, May 18, 2023.

13 William Oddie: Chesterton and the Romance of Orthodoxy. The Making of G.K.C. 1874-1908 (Oxford University Press), 2008.

14 Ian Ker: G. K. Chesterton. A Biography (Oxford University Press), 2011.

15 The G. K. Chesterton Papers, British Library, Add MS 73240 A 001-2.

16 Dorothy Collins: Datebook, transcribed by Nancy Carpentier Brown, unpublished. It is especially mentioned here because Ian Ker mentions the letter in his biography, and he draws a wrong conclusion, thinking that a greeting card from Undset to Chesterton dated 1931 meant that the meeting had taken place by then. However, the greeting card had accompanied a copy of her translation of The Everlasting Man into Norwegian as a gift to Chesterton.

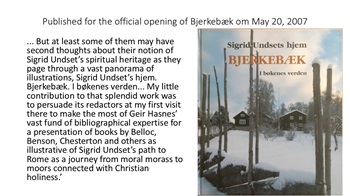

17 Geir Hasnes: “The Catholic Church and Conversion”, Sigrid Undsets hjem Bjerkebæk. I bøkenes verden, ed. A. Åslund et al. (Lillehammer: Maihaugen), 2007, pp. 138-139.

18 G. K. Chesterton: Den katolske kirke og konversion, translated by Ebba Svarstad (Oslo: Aschehoug), 1929: https://www.nb.no/items/1cef4d873cbf9b9c3092e0732afe99de.

19 Hilaire Belloc: Den katolske kirke og historien, translated by Ellen Faaberg (Oslo: Aschehoug), 1929: https://www.nb.no/items/7e4255c63b91cc2a704682d19d24301d.

20 The English Way. Studies in English Sanctity from St. Bede to Newman (London: Sheed & Ward), 1933.

21 Chesterton, a Seer of Science, p. 110.

22 Sigrid Undset: Through Moral Crises to Catholicism (Port Huron, MI: Real View Books), 2006.

23 Geir Hasnes: “Stanley Jaki and Sigrid Undset”, The Chesterton Review, 47 (3-4), 2021, pp. 385-91. https://doi.org/10.5840/chesterton2021473/470

24 Sigrid Undset’s Quest for Truth, p. 105.

Bibliography.

Hilaire Belloc: Den katolske kirke og historien, translated by Ellen Faaberg (Oslo: Aschehoug), 1929.

Hilaire Belloc: The Catholic Church and History (New York: Macmillan), 1926.

G. K. Chesterton: Den katolske kirke og konversion, translated by Ebba Svarstad (Oslo: Aschehoug), 1929.

G. K. Chesterton: Det evige menneske, translated by Sigrid Undset (Oslo: H. Aschehoug), 1931.

G. K. Chesterton: The Catholic Church and Conversion (New York: Macmillan) 1926.

G. K. Chesterton: The Everlasting Man (London: Hodder & Stoughton), 1925.

G. K. Chesterton: The G. K. Chesterton Papers, British Library, Add MS 73240 A 001-2.

Dorothy Collins: Datebook, transcribed by Nancy Carpentier Brown, unpublished.

Antonio Colombo: Email to the author, May 18, 2023.

Antonio Colombo: From Győr to Madrid, http://www.sljaki.com/biographies/america-colombo.html, 2018 and later.

Geir Hasnes: “Chesterton as Public Speaker”, The Chesterton Review 47 (1-2), 2021, pp. 63-75.

Geir Hasnes: G.K. Chesterton. A Bibliography (Kongsberg: Classica), 2022. Three volumes.

Geir Hasnes: “Sigrid Undset and the Saints”, StAR. Saint Austin Review 21 (6), 2021 (Houston: The Center for Cultural Renewal), pp. 4-7.

Geir Hasnes: “Sigrid Undset i bøkenes verden”, Gymnadenia Årsskrift (Lillehammer: Sigrid Undset-selskapet), 2008, 6 unpaginated pages.

Geir Hasnes: “Stanley Jaki and Sigrid Undset”, The Chesterton Review, 47 (3-4), 2021, pp. 385-91.

Geir Hasnes: “The Catholic Church and Conversion”, Sigrid Undsets hjem Bjerkebæk. I bøkenes verden, ed. A. Åslund et al. (Lillehammer: Maihaugen), 2007, pp. 138-139.

Stanley L. Jaki: Chesterton, a Seer of Science (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press), 1986.

Stanley L. Jaki: Sigrid Undset’s Quest for Truth (Port Huron: Real View Books), 2007.

Stanley L. Jaki: The Relevance of Physics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), 1966.

Ian Ker: G. K. Chesterton. A Biography (Oxford University Press), 2011.

William Oddie: Chesterton and the Romance of Orthodoxy. The Making of G.K.C. 1874-1908 (Oxford University Press), 2008.

Sigrid Undset: Saga of Saints (London: Sheed & Ward), 1934.

Sigrid Undset: Through Moral Crises to Catholicism (Port Huron, MI: Real View Books), 2006.

Maisie Ward: The English Way. Studies in English Sanctity from St. Bede to Newman (London: Sheed & Ward), 1933.