Fr Stanley Jaki argued that science is about quantities. Anything immeasurable, including God, it can neither prove nor disprove.

Seven years have passed since the death, on April 7, 2009, of Fr Stanley Jaki OSB, a great fighter for Catholic truth and a world-ranking authority on science and religion.

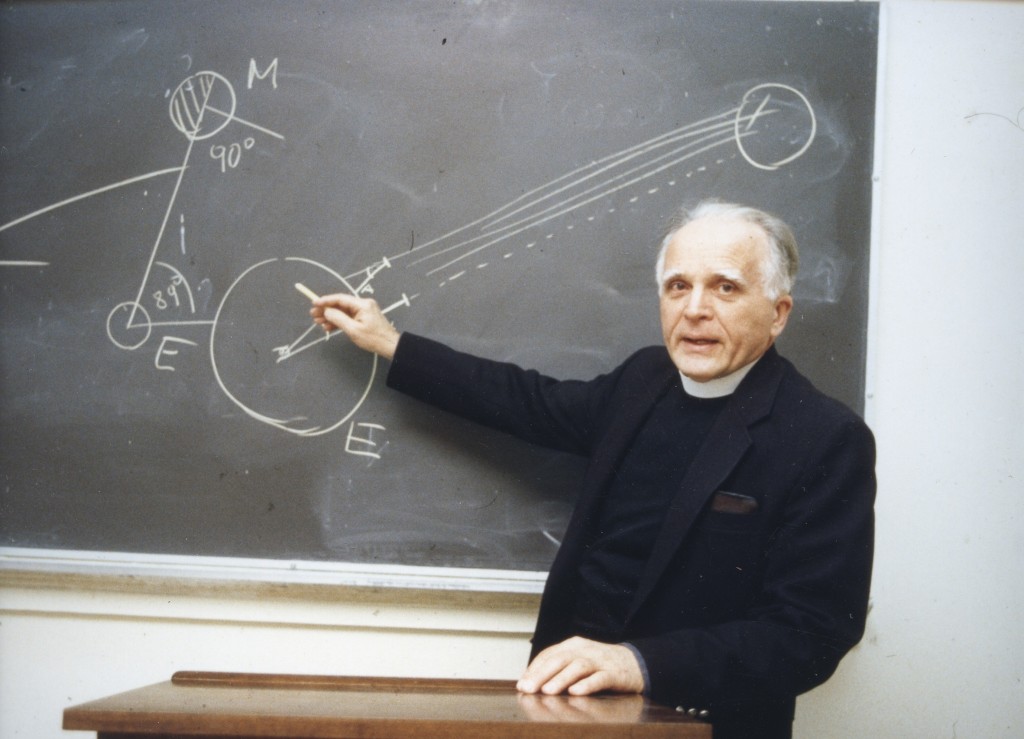

I had the privilege of working with him for five years. He was the author of more than 50 books and over 400 articles. He was the recipient of many honours, most notably as a member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences and as a winner (in the company of Mother Teresa of Calcutta and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn) of the Templeton Prize, given for outstanding progress in religion.

Never was the witness of Fr Jaki more needed than now. The present time seems to be open season for scientists to attack Christianity. The media devote much time to promoting programmes featuring Dawkins, Hawking, Dennett, Harris and Atkins, to name only the usual suspects. What is needed is a rebuttal of their errors on the relationship between science and religion, something all the more necessary for good and faithful Catholics. This is something that Fr Jaki’s works are perfectly set up to do.

Yet he has been sadly neglected when what is needed in the battle against the so-called New Atheists is a series of simple and direct responses for which he was so renowned.

I recall a perfect example of this when Fr Jaki and a philosopher, a Fellow of one of the Oxford colleges, were having a conversation. The philosopher announced that he didn’t believe in free will and was a determinist. Fr Jaki immediately asked of him: “Did you say that freely?” Result: a series of stutters and the response: “I’ll have to get back to you on that!”

So here is a short attempt to cover a number of basic principles, all taken from Fr Jaki’s writings, that are crucial to arguing our corner in the debate on science and religion. It begins with an appreciation of the nature of science, by which Fr Jaki means, of course, exact science, notably physics, astronomy and chemistry.

“Science derives its exactness from measurements which is the application of quantities, or numbers. Numbers are the specifically exact notions among all notions the human mind is capable of forming. An action may be more or less emphatic, goodness admits grades and shades but, say, the number five cannot be more or less five. Herein lies the crux of all talks about science and religion, and even about science and any non-scientific field of inquiry.”

Exact science, then, is about quantities, nothing more and nothing less than just quantities. So, can the existence of God be proved by science understood in this sense? Of course not.

“Since a scientific proof must rest on measurements, the proof would imply that God can be sized up by callipers, weighed in balance, confined to a test tube, scanned by photon beams, pictured in holographs, and, for good measure, described in tensor equations.”

But whenever an assertion contains non-quantitative propositions, and it does so often, science becomes irrelevant. Exact science, then, is extremely limited in its applicability, although it is applicable everywhere where there is matter (and we must not forget the massive role that science plays in this area).

Here is the answer to the New Atheists, who are making the mistake of dealing with matters outside their field of exact science. It is essential, then, that they are relentlessly pressed whenever they bring science into connection with a non-scientific subject, such as God.

“Scientists should be viewed as acting in a most arbitrary manner when they touch on matters that are not quantitative. If scientists want to grasp the purpose of anything, they sin against the logic of science if they try to fathom purpose through science, unless they find a way to measure purpose. The question of free will is not something for science to handle. There are no quantitative units in which to measure free will. There are no two grams of purpose and five nanoseconds of free will.”

So the most fundamental rule which should govern all reasoned talk about the relation of science and religion is that quantities form one conceptual domain, and all other concepts another.

The question of origins can be dealt with in the same way. Coming into existence and going out of it would become a scientific topic only when a method of measuring the ‘nothing’ is invented. Thus, it is clear that science, so fruitful in its own field, can say nothing about many matters that are most important for man.

It follows, then, that neither can science disprove the existence of God. What it can do, and this is important in the present context, is to provide us with ever vaster amounts of quantitative data about specific things. It is for philosophy alone to provide the reasoning which shows that the specific nature of things as seen everywhere is tied to a coherent totality, just as specific, and that it can therefore be accounted for only by a primordial creative act of God.

Moving in this way from finite, contingent things to an infinite reality as the ground of the former’s existence is admittedly not a proof in the sense in which proofs are meant in science. It is rather something from which an inference may be drawn. Not a knock-down argument, then, but nevertheless a powerful process of reasoning.

It is inevitable that the topic of Darwin and Darwinism figures significantly in the media’s portrayal of this subject area. Some contributors go as far as to say that Darwin’s theory of evolution disproves the existence of God. It does nothing of the sort.

Again the key to understanding is to appreciate the nature of science and its relationship with other disciplines. The theory is a scientific one, because, in principle at least, its two main factors (that the offspring are always slightly different from the parents, and that the physical environment has a differential impact on the offspring) can be evaluated quantitatively. Quantities make a science exact. Anything else in it is philosophy.

So, this is the reason, according to Fr Jaki, why credit should be given to Darwin for putting evolutionary speculations on the road toward the status of exact science. Are there any weaknesses in Darwinism? Fr Jaki indicates that there are many, far more than can be covered in a short article of this kind. He instances the fact that Darwin’s theory leaves no room for the mind, to say nothing of love. He points to the statement of another Darwinist, JBS Haldane: “If my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain, I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true. They may be sound chemically, but that does not make them sound logically. And hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms.”

The major factor in the present context is that when the New Atheists use Darwin’s theory as a stick with which to beat the religious viewpoint, as a means of showing that there is no purpose in the universe, they are using it not as a science, but as an ideology. Once again, it is the non-quantitative matters that are being referred to and these are not amenable to the scientific method.

As Jaki points out, “For all its value as a scientific theory of evolution, Darwinism, if taken consistently, cannot say anything about existence, purpose, and mind.” But Darwinists will not grant this, precisely because for them the theory is also an ideology, and one that is brazenly materialistic.

It is amusing here to note the remark made by AN Whitehead regarding the approach taken by Darwinists of the kind referred to here, namely that “those who devote themselves to the purpose of proving that there is no purpose constitute an interesting subject for study.” When Darwinism is taken as ideology, it cannot be reconciled with Christian belief, whereas the scientific theory can, because it cannot touch on the basics of that belief.

It is sad that Fr Jaki is not as well known as he should be. He is not the first great mind not to have been used to the full by the Church (Newman was another, of course). Whatever the reasons behind this, there can be no doubt that he has shown that contemporary science is as much about an anti-religious agenda as about discovery.

To Fr Jaki, the present problems faced by the Church were so serious that “one has only one choice: to fight”. He worked ardently to give Catholics the weapons with which to counter secular materialism and promote the Catholic faith.